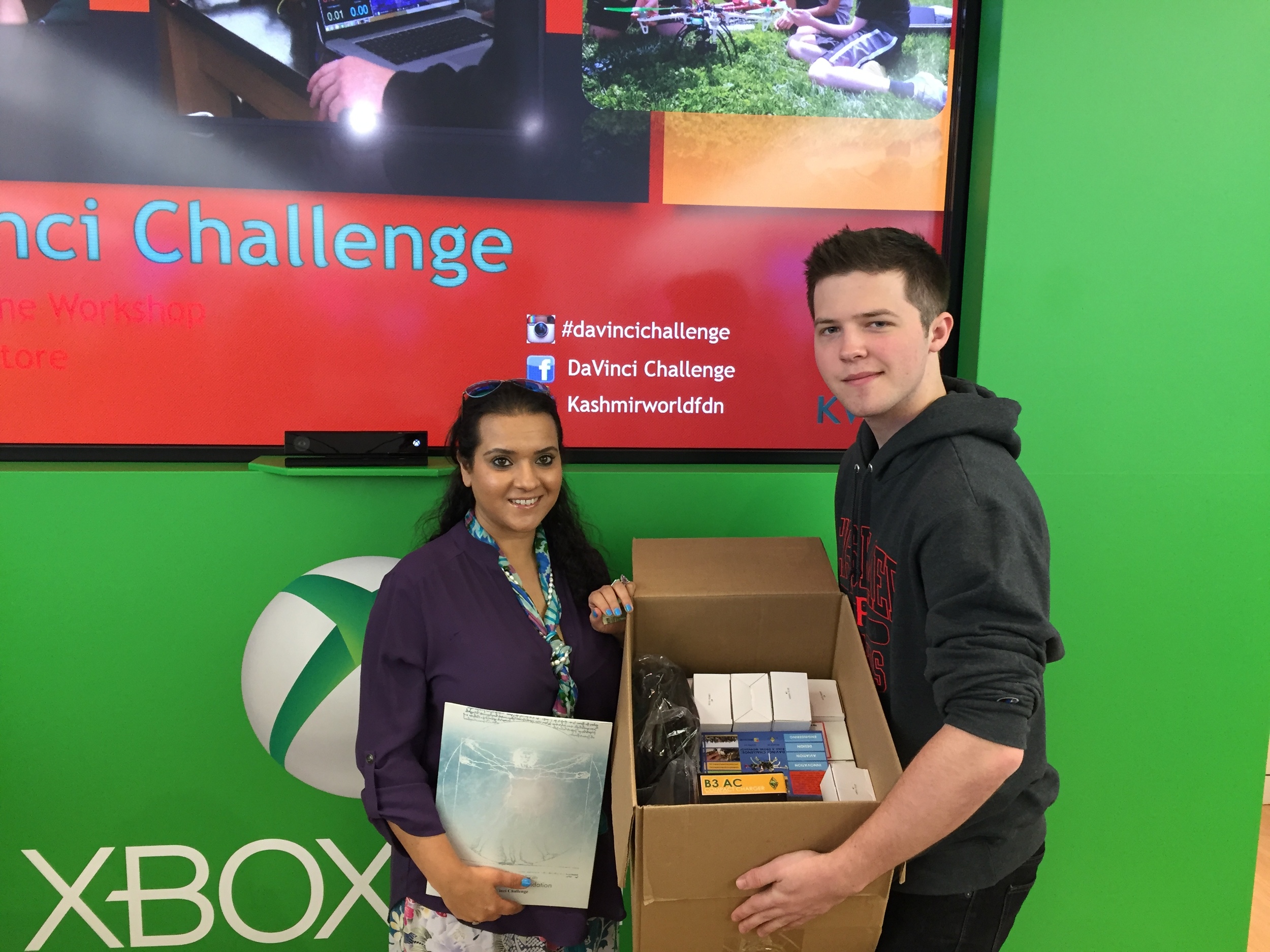

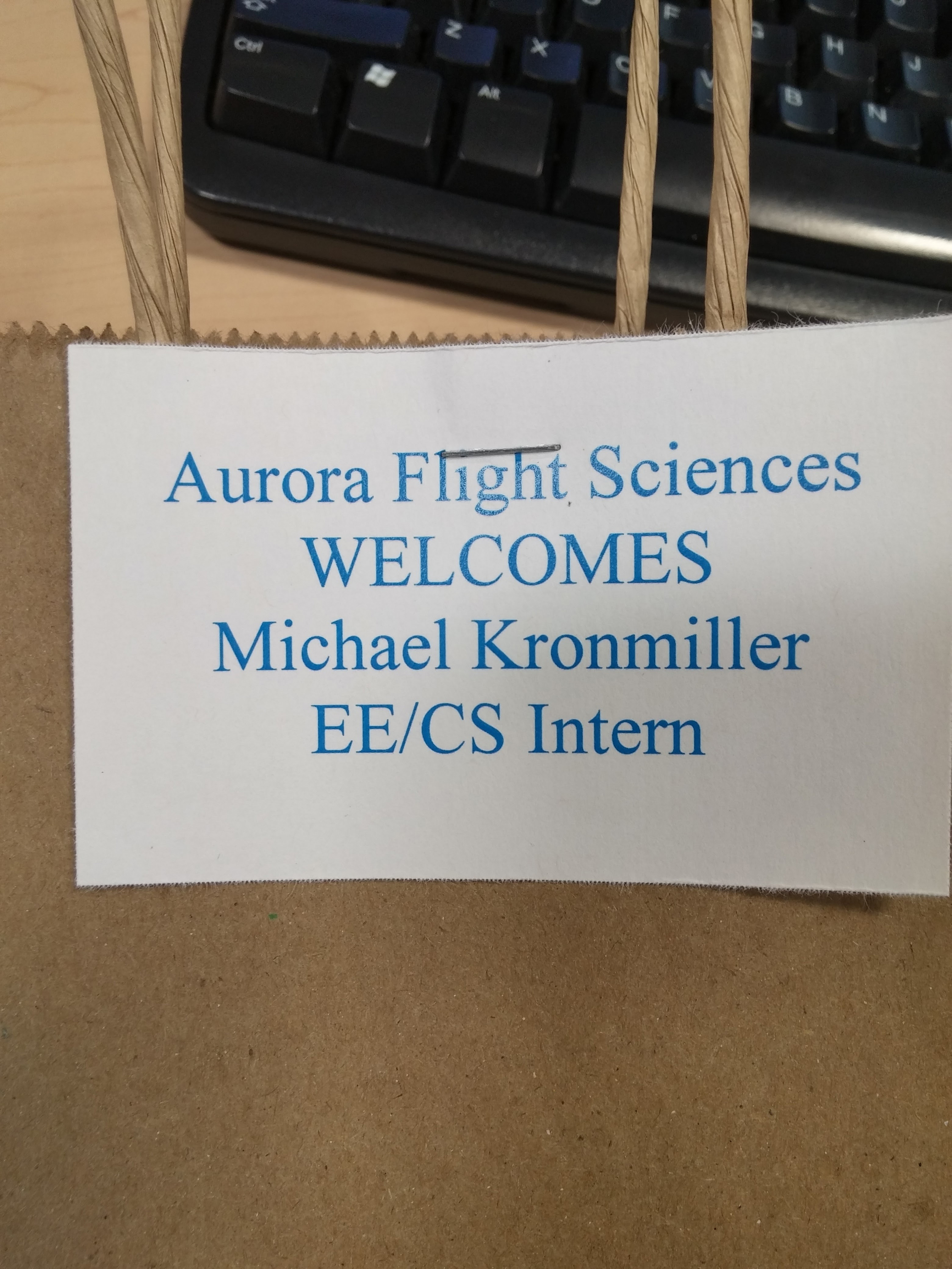

My name is Michael Kronmiller. I am an eleventh grade student engaged in a formal STEM project aimed at developing sensor-equipped sUAS to locate avalanche victims and inspect critical infrastructure in Nepal. If my project succeeds there, a country with extreme environmental conditions and limited financial resources, then the technologies being developed can be applied virtually anywhere else in the world. See nepalrobotics.org.

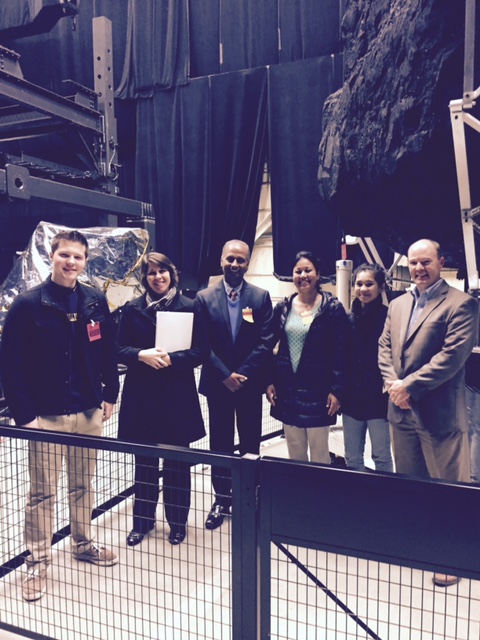

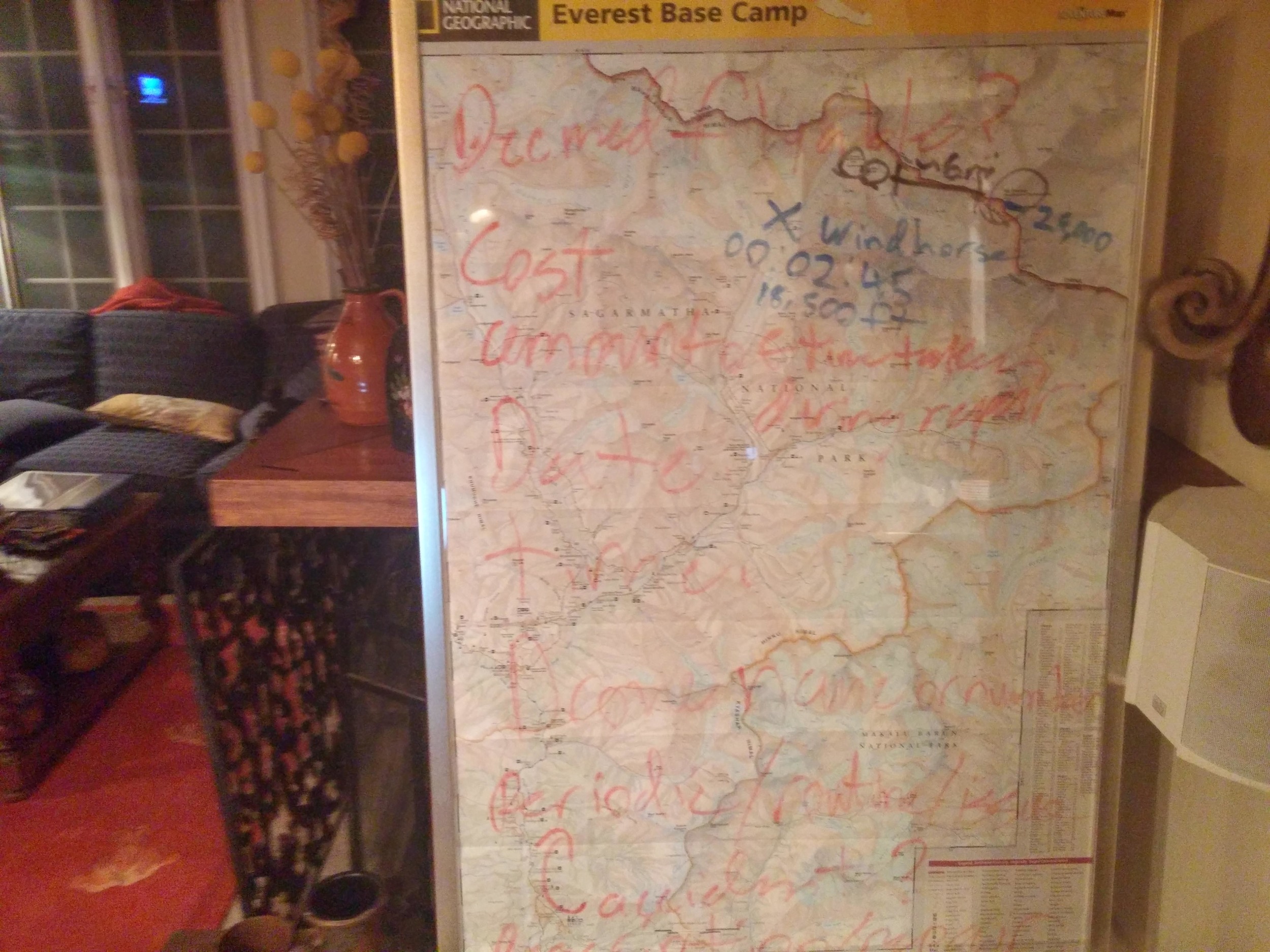

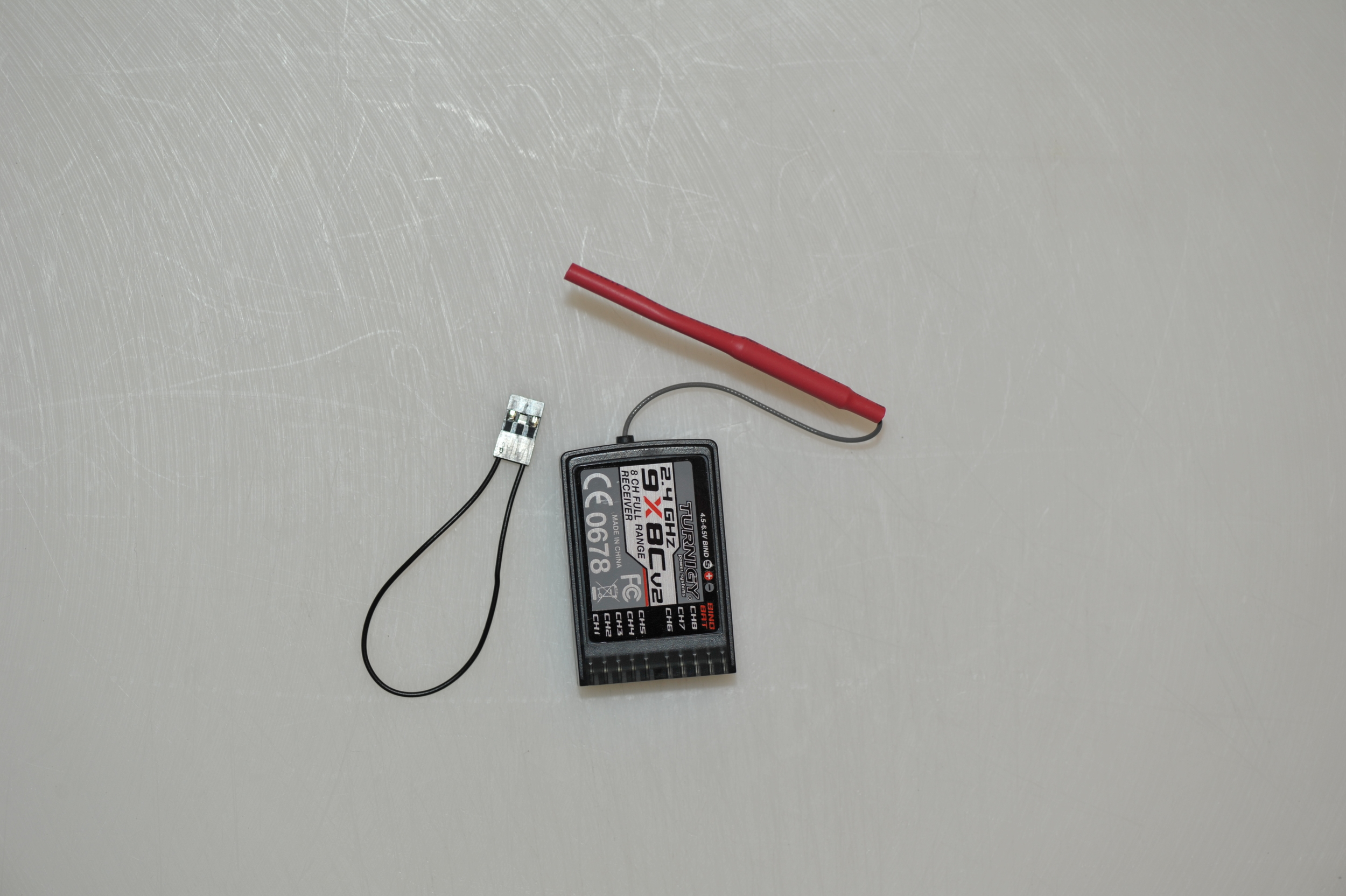

In March of this year, one of my project advisers and I traveled to Nepal in order to conduct test operations of simple drones from Kala Patthar at Mount Everest, and in the valleys and hills of the Annapurna Region, as well as to initiate direct consultations with the school in Kathmandu that is collaborating with mine in Potomac, Maryland. The drone tests were successful, despite the limitations imposed by export controls, and by the restrictions and uncertainties for flight testing in the United States, which I will address in this response to the FAA’s request for comments.

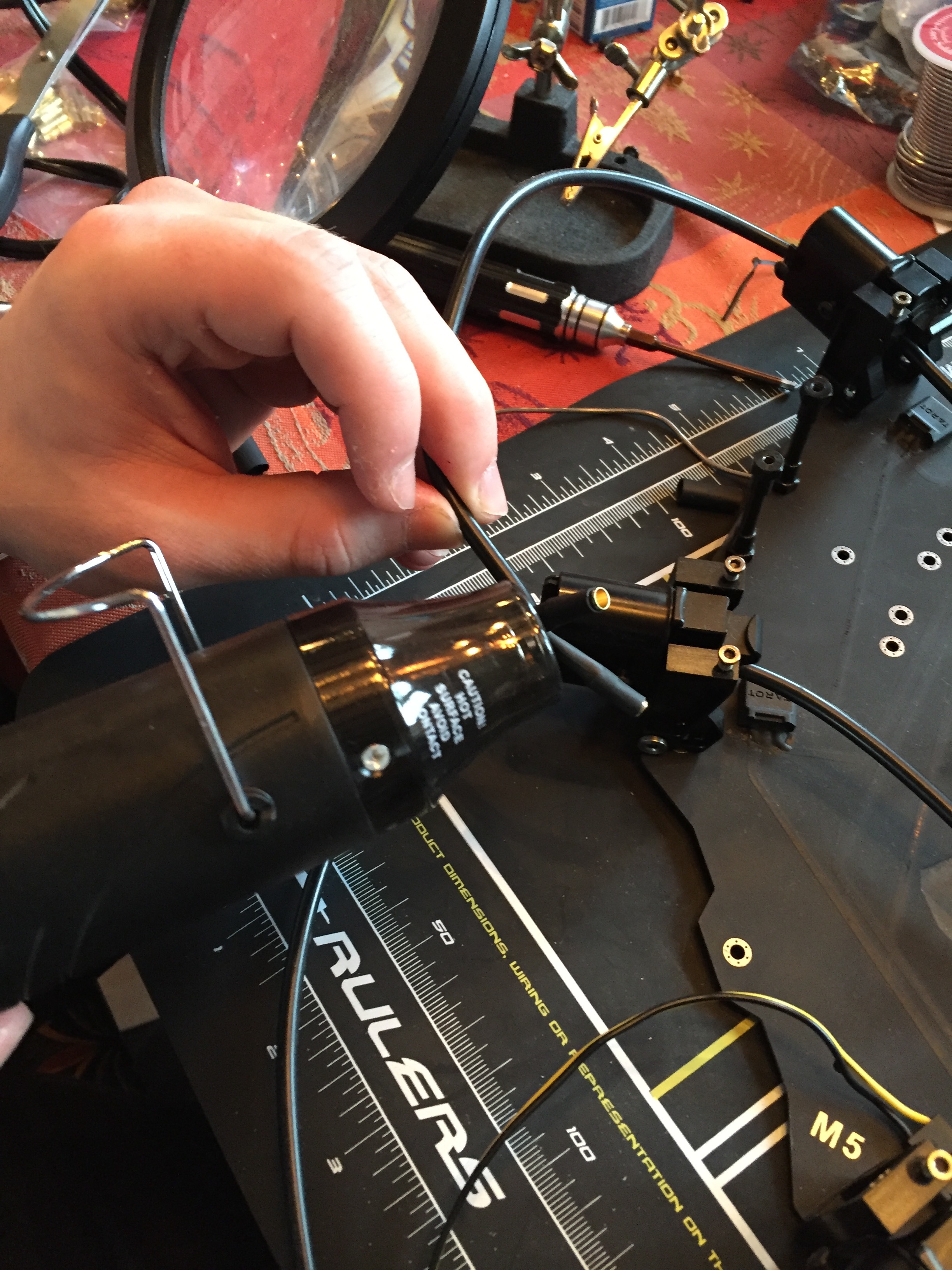

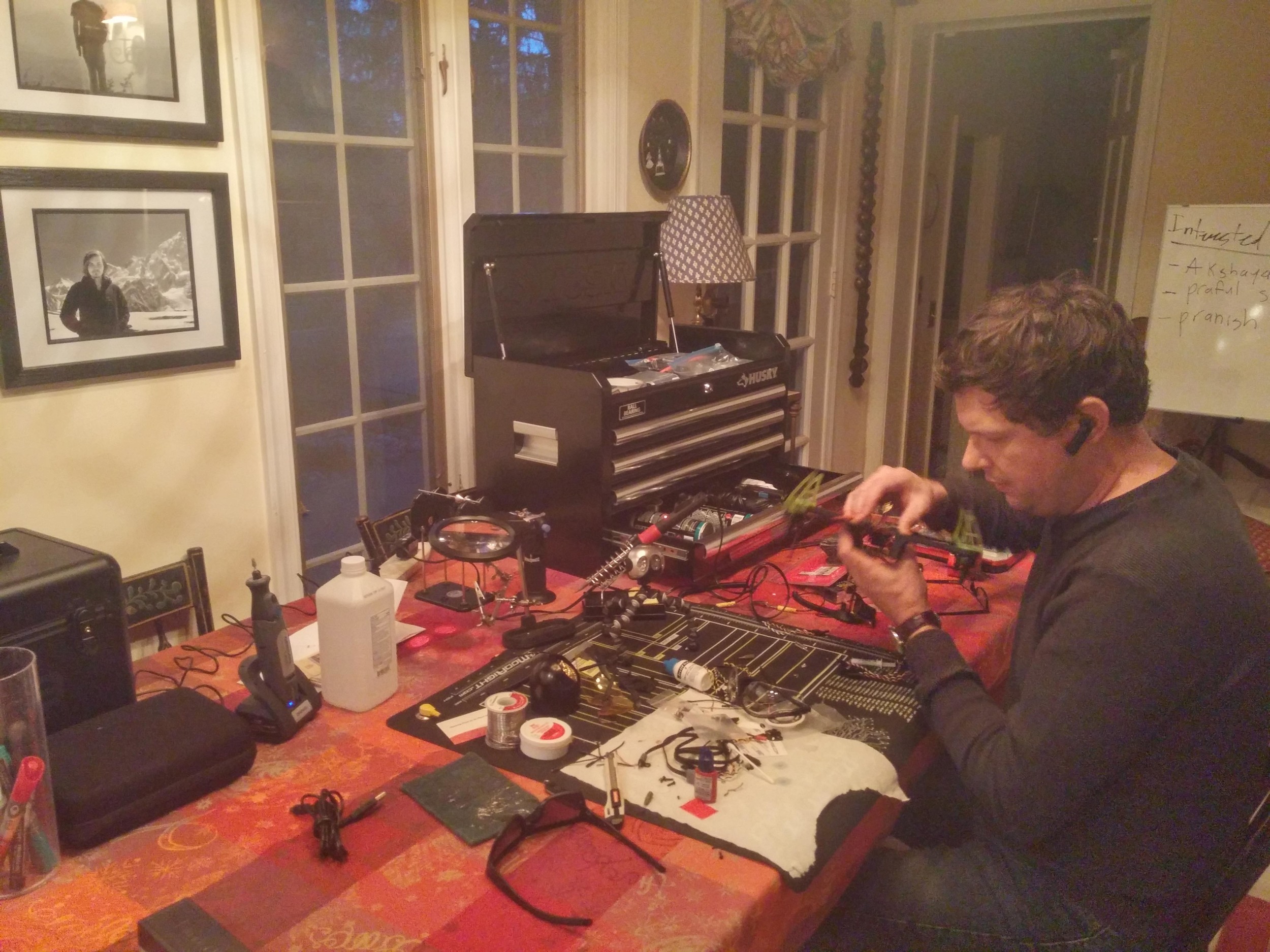

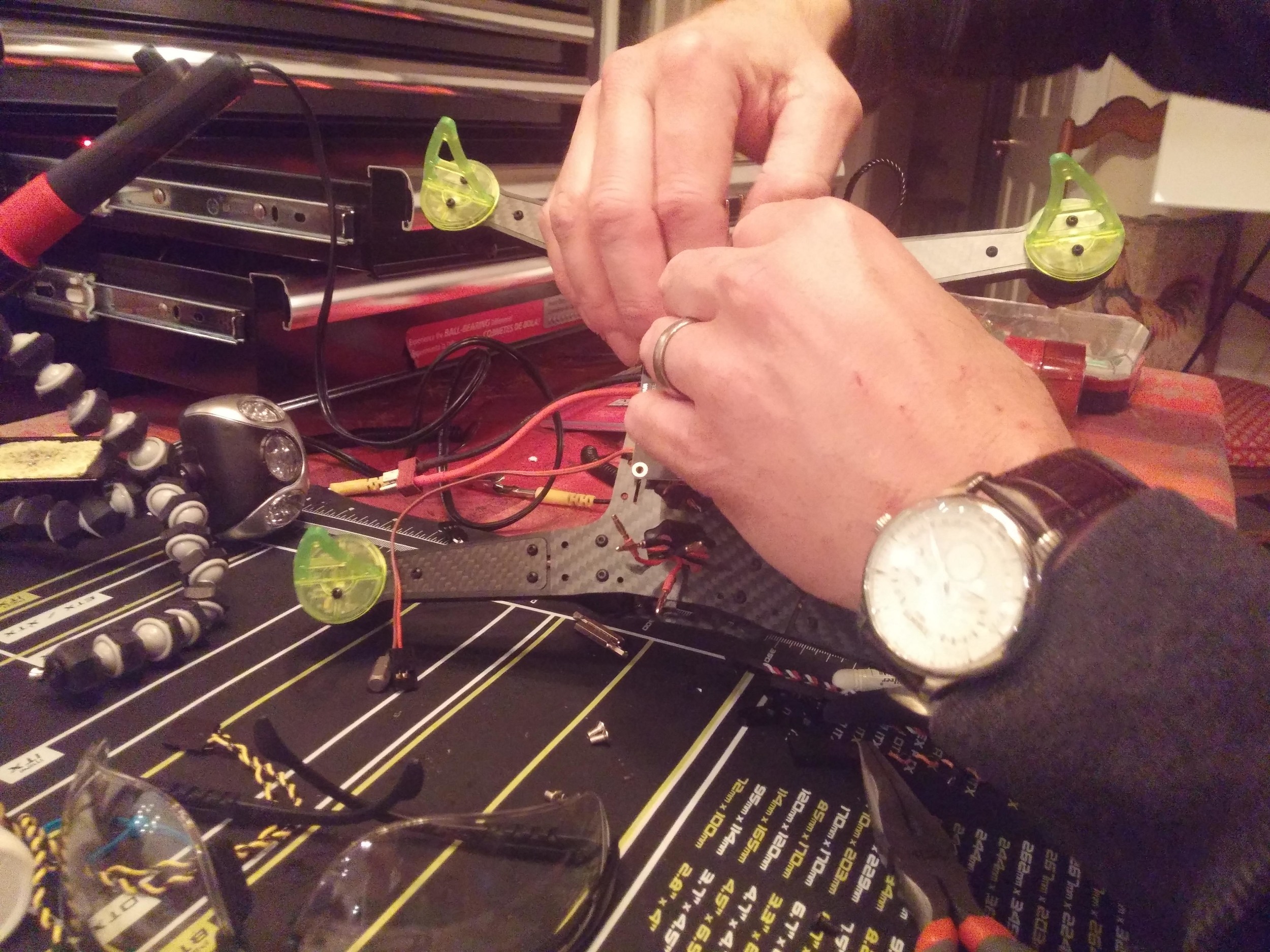

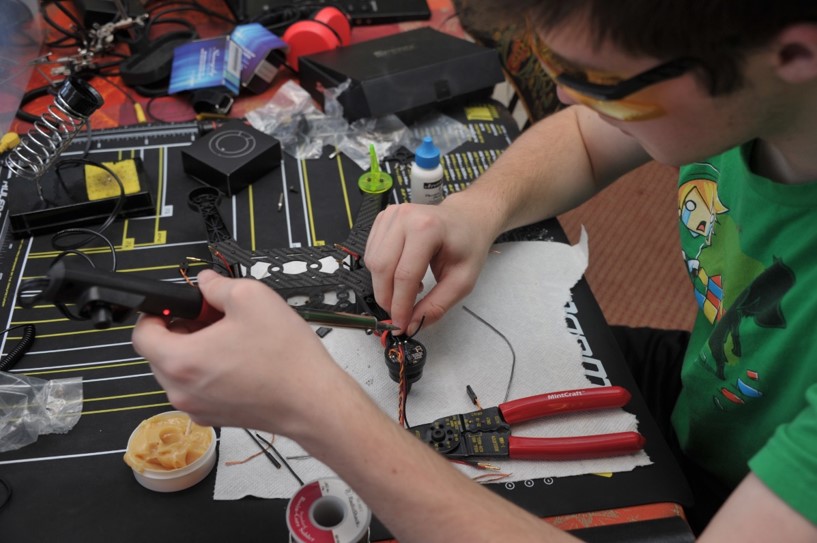

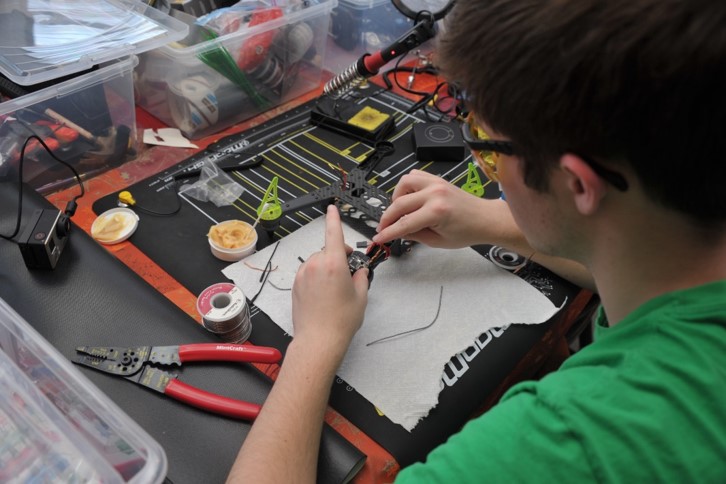

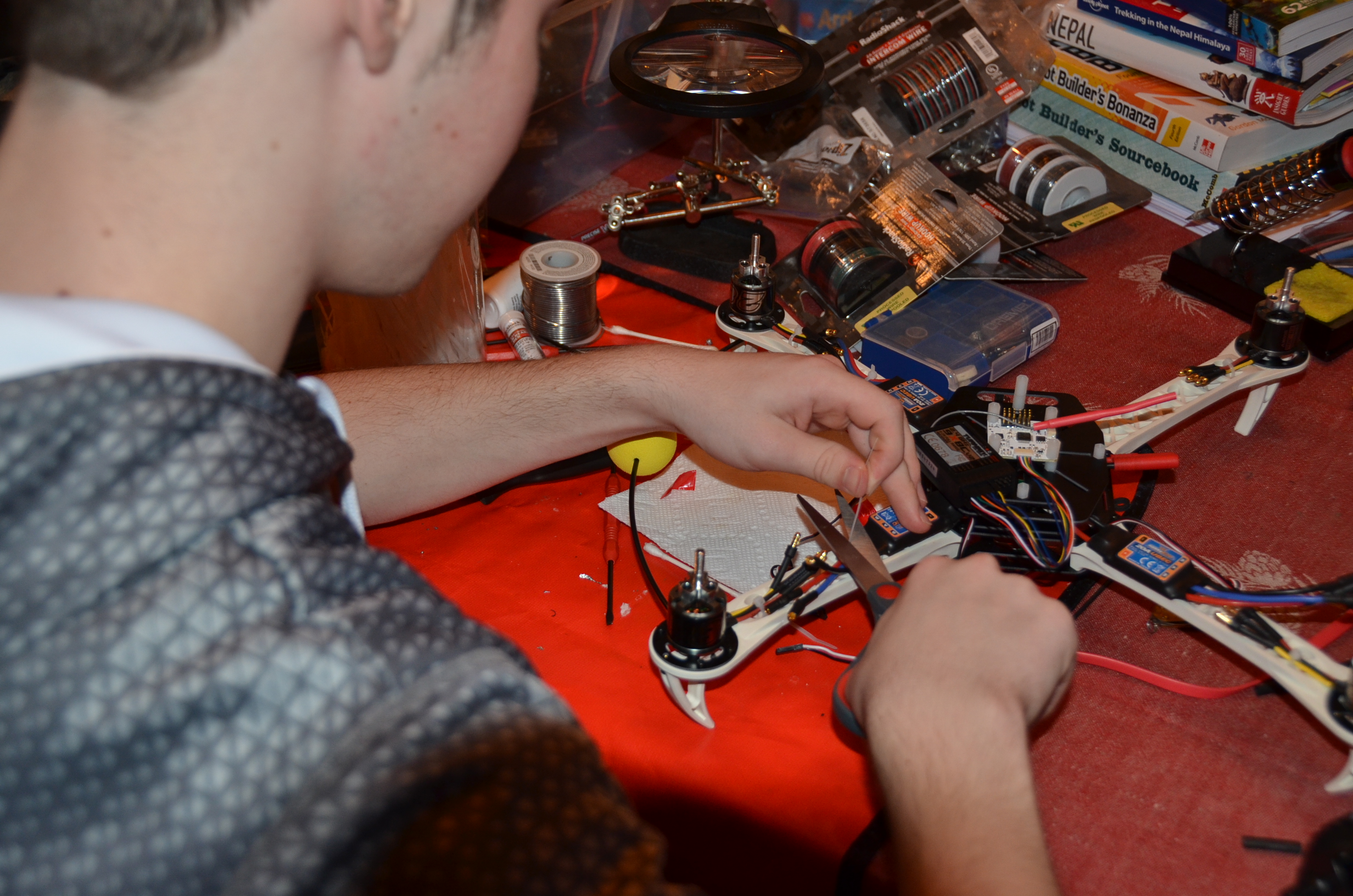

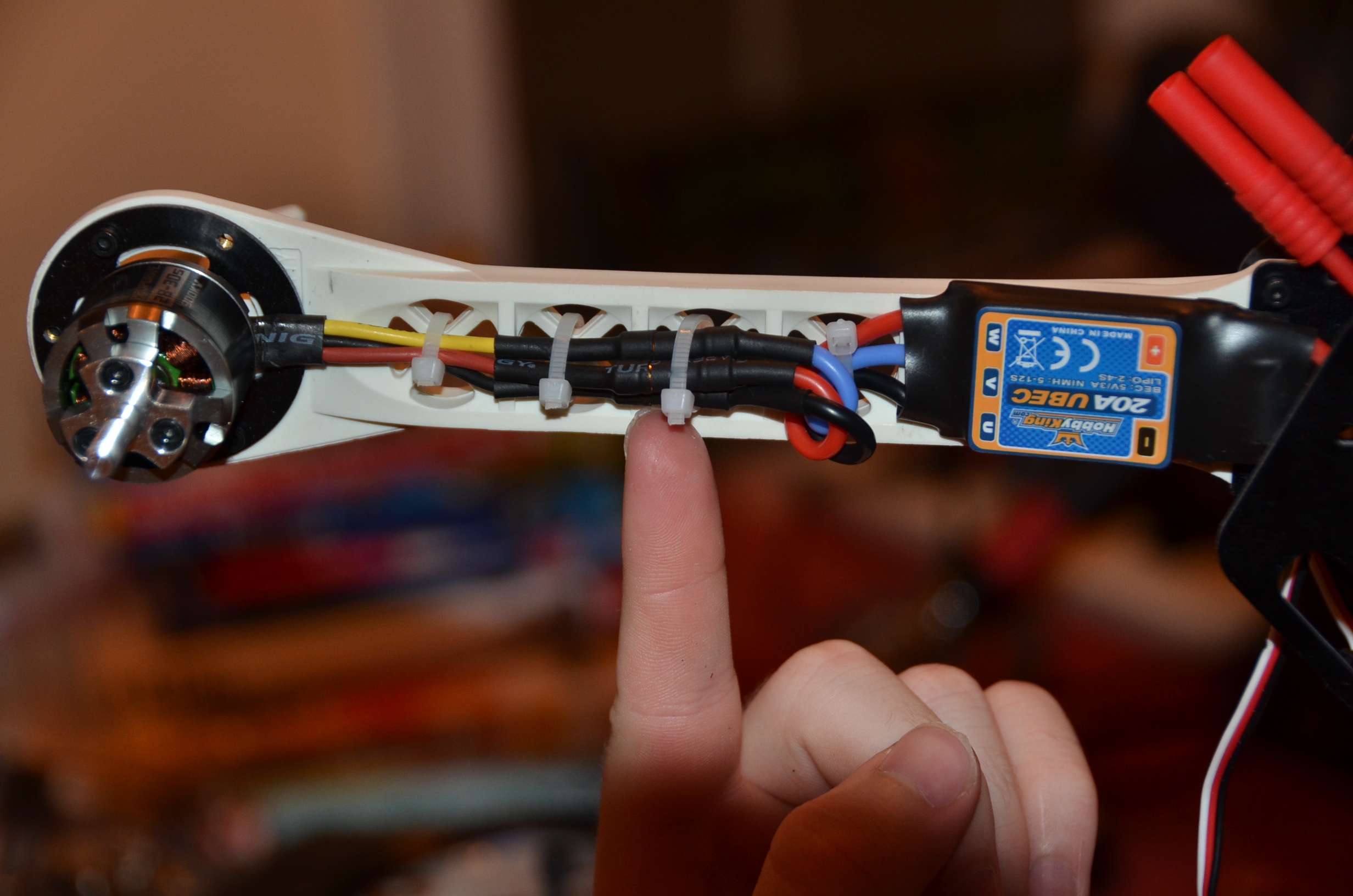

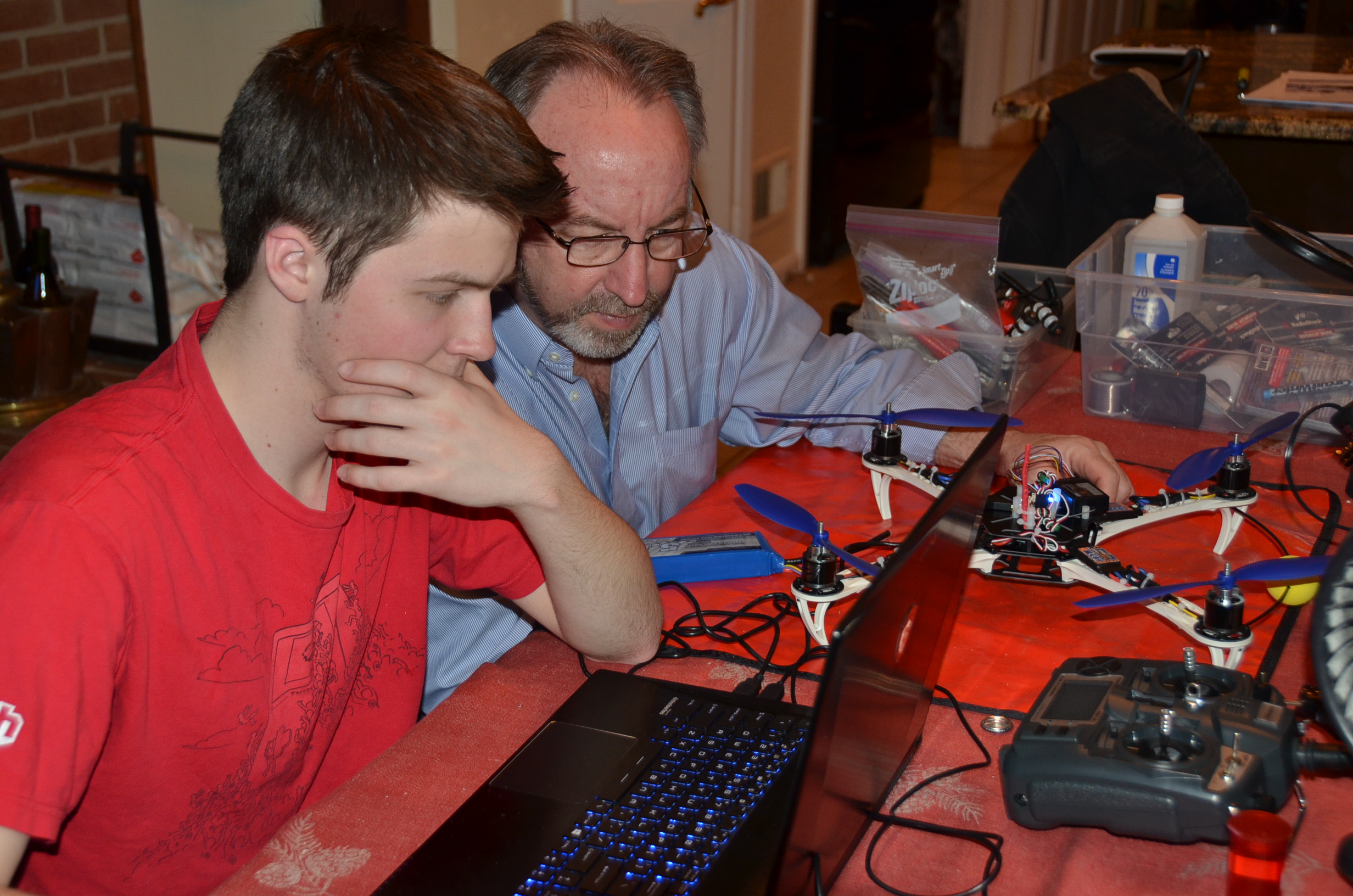

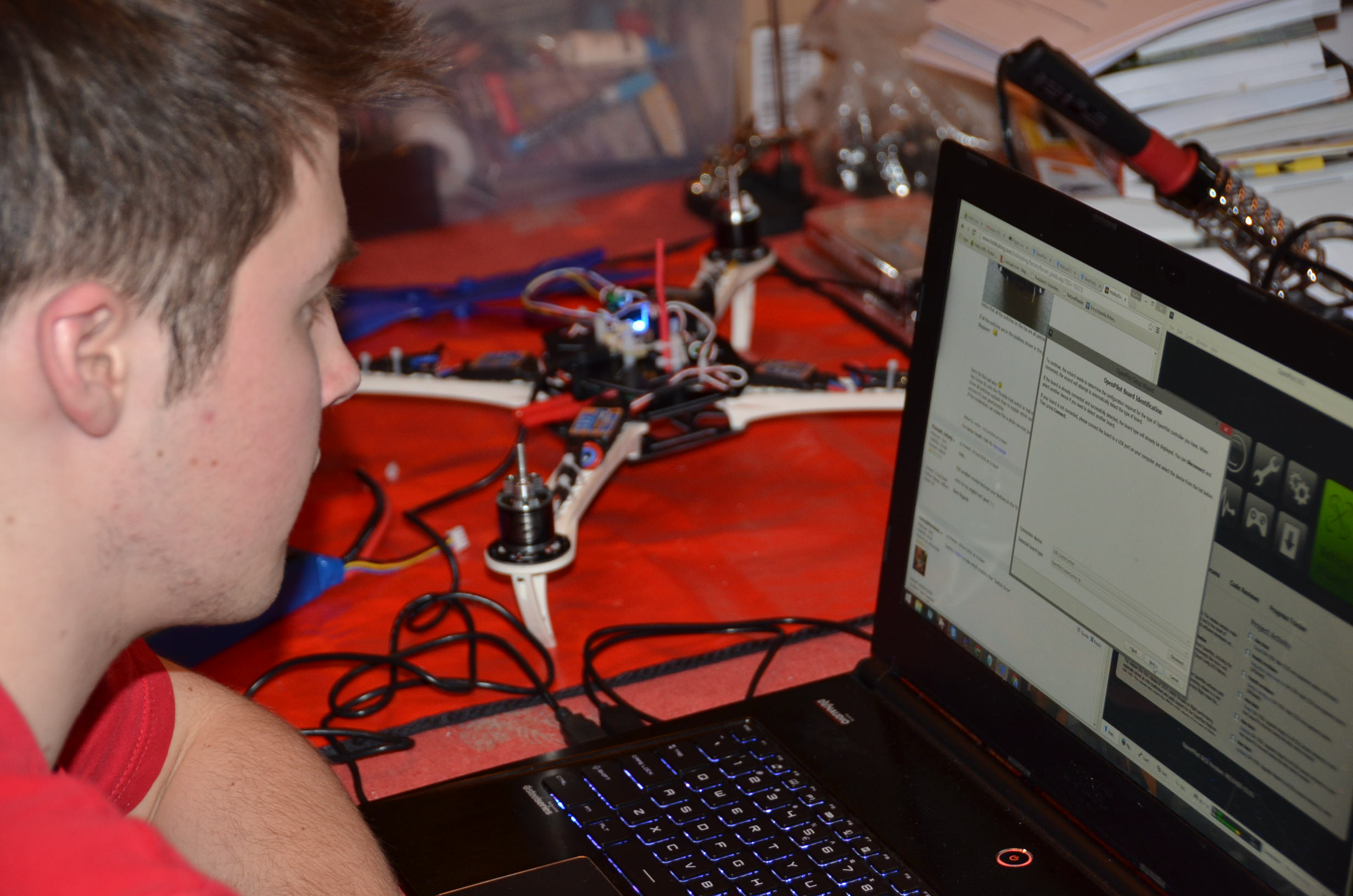

The short of it is that, due to concerns expressed by my school’s attorney regarding the legal situation for sUAS flights in the NAS, I was not permitted to conduct flight tests outdoors on the school premises. For obvious risk prevention reasons, flying indoors at the school was also not an option. That left me in the position of having to test fly the drones, then under development, away from the STEM resources of the school, and inside the confines of my home, which presented a completely unrealistic and suboptimal environment for sUAS operations.

The point is that it is extremely difficult for students and their schools to conduct worthwhile sUAS R&D in the United States. Moreover, under the proposed rule, the burdens, costs, and flight restrictions associated with compliance would perpetuate a situation that already deters young scientists, engineers, and technologists from entering this field. Such a result cannot be in the national interest.

To be clear, the proposed rule, if promulgated, would pose serious problems for my school project, as it advances to more capable drones requiring more rigorous and realistic flight testing. In fact, many potentially valuable, advanced technology sUAS educational projects like mine would never be initiated.

After a lengthy meeting with my Head of School, the Head of the Upper School, and the school’s attorney, I decided to proceed with my project, although I knew that, for lack of flight testing in the NAS, the drones would be challenged to operate in the high altitude conditions of Everest and the jungles of the Annapurna Region. It was an expensive risk that should not have to be repeated.

Based on my experience, and given that the FAA has articulated a need for academic research, development, and testing as an important goal in its proposed rules, I suggest a two-tier approach to sUAS flights for academic purposes:

First tier–The test flight work that needs to be done for relatively simple academic sUAS projects could be accomplished under the guidelines that apply to hobby and recreational flying. It is senseless that a young hobbyist and a student can fly exactly the same drone in exactly the same way, while the hobbyist is currently subject only to limited guidance, but the student is subject to the rigors of the regulatory regime maintained for other users, and with the adoption of the proposed sUAS rule, would be subject to a regime that is more complex, burdensome, costly, and restrictive than the hobbyist/recreational guidelines. I think the case can be made that academic research is at least as valuable to society as is recreation. Therefore, I suggest that the FAA adopt by regulation for simple academic sUAS flights the guidelines that apply to flights for hobby and recreational purposes.

Second tier–For more ambitious flight testing, that cannot be conducted in compliance with the provisions of the guidelines that would be adopted by regulation for academic sUAS flights, more extensive requirements could be appropriate. However, I would urge that the FAA take into account the fact that an academic environment is, by its nature, structured and supervised, and that safety is always at the forefront of any school activity involving risk. Accordingly, there should be greater flexibility provided for this category of sUAS flights, than is provided for flight operations not subject to the discipline of academia. Moreover, students and their schools should not be confronted with complex, burdensome, and costly requirements that will have the effect of deterring research and development for more capable drones under development to perform more challenging tasks. Where requirements and restrictions are imposed, there should be provisions for waivers that would provide appropriate flexibility and eliminate requirements and restrictions that are unnecessarily costly and otherwise burdensome. If it is not to be self-defeating, the waiver process should be a streamlined as possible.

Although it is outside the scope of the request for comment, there is a good case to be made for a new, statutory regime exclusively applicable to academic flight testing of sUAS. In the meantime, it is important that promising students with promising sUAS projects be not only allowed, but also encouraged, to pursue goals that will serve our nation. This should be the touchstone for the final rule as it applies to academic sUAS projects.